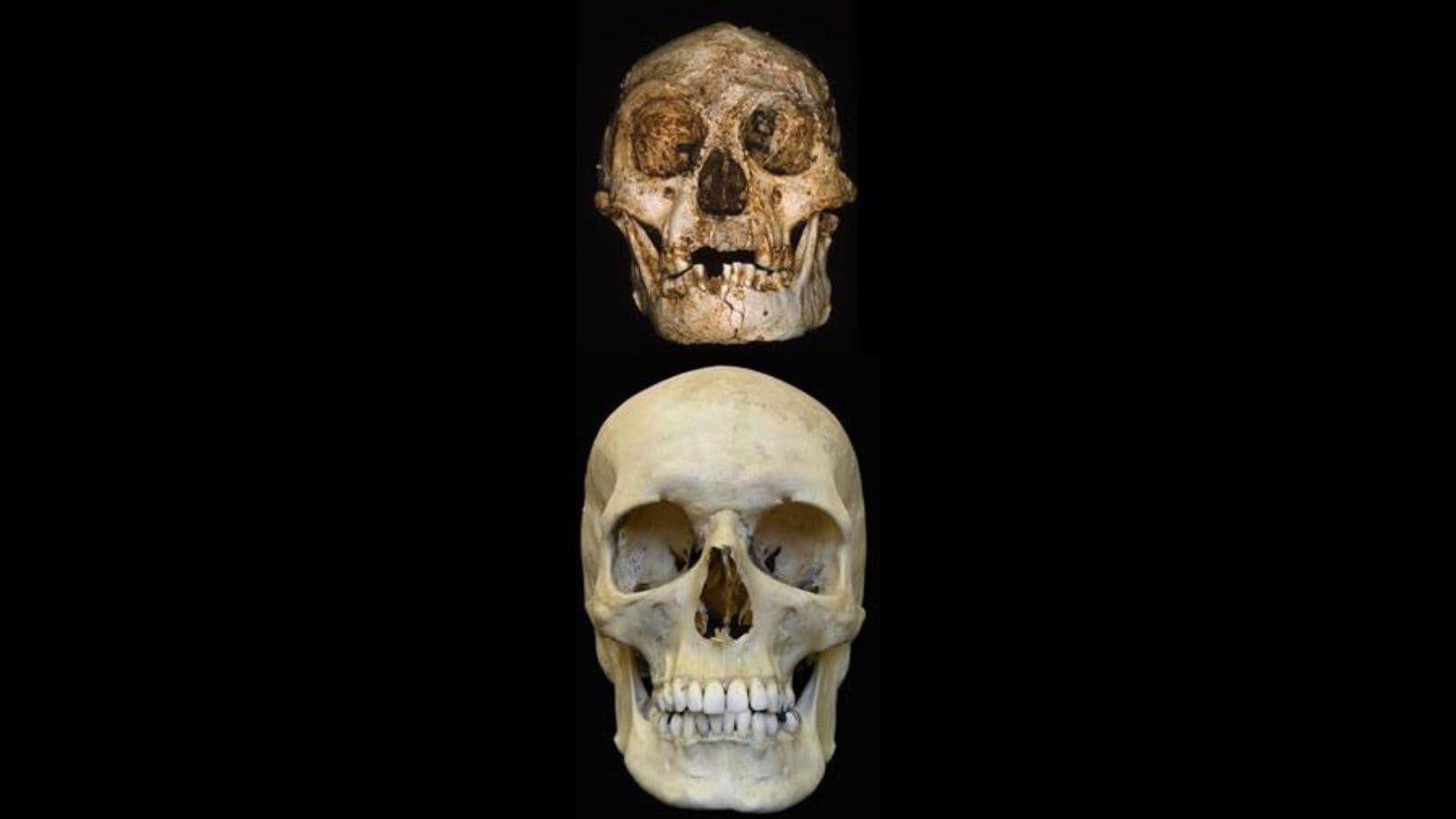

The mysterious demise of Homo floresiensis, the tiny human species often dubbed hobbits, may be tied to a long-lasting decline in rainfall that reshaped life on the Indonesian island of Flores around 50,000 years ago. According to new research, the drying climate likely reduced the availability of prey, pushing the hobbits into areas where they may have come face-to-face with expanding groups of Homo sapiens.

Researchers stress that drought was likely just one part of a complex collapse. A volcanic eruption that took place around the same time may also have delivered a devastating blow to the already struggling population.

Since the discovery of Homo floresiensis in Liang Bua cave in 2004, scientists have been trying to piece together how this small-bodied human lived and what ultimately caused its extinction. In the new study, published Monday in Communications Earth & Environment, scientists report that rainfall on Flores dropped sharply 50,000 years ago, a shift that appears to overlap with a decline in stegodon, an extinct elephant relative that formed a major part of the hobbits’ diet.

Reconstructing an ancient drought

To track how rainfall changed over time, the team analysed a stalagmite from Liang Luar, a cave near the site where the hobbits’ fossils were found. Stalagmites grow as mineral-rich water drips and evaporates, leaving behind layers of calcium carbonate and tiny traces of other elements. During dry periods, these rock formations grow more slowly and contain more magnesium relative to calcium, creating a chemical record of shifting climate conditions.

Also Read: Study changes picture of evolution, says humans lived in southern Africa for 100,000 years in genetic isolation

Using these measurements, the team found that average annual rainfall fell from about 61 inches (1,560 millimetres) 76,000 years ago to roughly 40 inches (990 mm) by 61,000 years ago. That reduced level appears to have persisted until around 50,000 years ago, the moment when a volcano on the island erupted, coating Flores in a layer of debris.

The decline of stegodon

The researchers then examined stegodon teeth from archaeological layers and found that the animals’ numbers had dropped steadily between 61,000 and 50,000 years ago, disappearing entirely after the eruption. With their primary prey dwindling, the hobbits would have struggled to find enough food.

Story continues below this ad

Lead researcher Nick Scroxton, a hydrology and paleoclimate specialist at University College Dublin, told the Live Science website that shrinking water sources likely forced stegodon to migrate towards the coasts, and the hobbits may have gone with them in search of food. “If the stegodon population were declining due to reduced river flow, then they would have migrated away to a more consistent water source,” he said. “So it makes sense for the hobbits to have followed.”

A collision with modern humans

This movement towards the coast may have brought Homo floresiensis into contact with groups of Homo sapiens expanding through the region at the same time, potentially leading to competition over increasingly scarce resources or even conflict. Combined with the volcanic eruption around 50,000 years ago, the hobbits may have faced conditions too harsh to survive.

Experts not involved in the study say the findings paint a compelling picture. Julien Louys, a palaeontologist at Griffith University in Australia, noted that even modest rainfall reductions can have outsized effects on a small island. “There’s only a limited amount of space on an island, and only so many types of environments that can be harboured,” he said. As conditions dry out, animals can’t escape to larger landmasses, and those few remaining refuges quickly become overcrowded.

Debbie Argue of the Australian National University also praised the research, saying it offers valuable insight into how rapidly changing climate conditions shaped life on Flores. “The paper gives us an excellent insight into a changing climatic environment in the region,” she said, calling it an important addition to the growing understanding of past ecosystems on the island.